On a typical sunny afternoon in Santa Monica, I went to visit mother. When I opened the door, I found her on the floor of the entry hall, lying on her back with her eyes closed, as if she were dead. I was frightened, but I had to stay calm. With my hand bracing her tiny back, I lifted her into a seated position. She immediately woke up, saying “I don’t know what happened. I guess I fainted.” I scrutinized the back of her head. There was no sign of blood. I asked her if she was okay. She said, “I’m not hurt. Don’t worry Jerry. There’s no problem.”

Her cardiologist had warned us that her heart medications, at some point, would not work. I said, “Mom, I need to move in with you.” She was 91. It was time. She nodded yes. We didn’t have to discuss it —- just like all the other silent understandings, as far back as I could remember, both of us knowing without any need for words: there’s no other way — this is how it has to be.

From my early childhood, my mother’s world made up my entire world. I adopted

all her ways, her view of everything, her horizons. And I hated my father throughout my

childhood. During their argument-time at the dinner table, I latched onto her causes and desires, silently marching and singing to them. Father was always wrong. Especially when, as ruler of the home, he handed down his final decisions, like denying my mother’s simple requests, such as buying shoes for my brother and me. At that dining room table, my passion for justice was born.

Saying I was going to move in with mother sounds simple, but, in fact, the decision climaxed a long and tortuous journey. After I left for college, as a boy really, I never returned, always living far away. But we visited regularly on birthdays and holidays, and a few times we vacationed together. When my father died, I began to think about ending my exile and return to mother. But I put off acting on the thought. I had been away for 30 years. I was a lawyer living in Denver. It would take time to close down the law practice.

Mother and I now spoke often. I asked her what it was like living alone after being with father for 59 years . She said, “I’m just fine living alone.” But I heard a quaver in her voice. Then she told me in a steadier and stronger voice, “You are my strength!” I knew, right then, that I would have to move to Santa Monica. I didn’t tell her, but said, “Mom, I’m going to come out there every month to spend a few days with you.” I had no idea at this point who would need help and who would provide it.

On my third visit to mother, on a Sunday morning in June, I felt very weak getting out of bed. In the bathroom, bending over the sink, I struggled to wash my face. When I tried to lift my hands higher to comb my hair, it was only on the third try that I succeeded.

A few hours later, I found myself in the emergency room of Kaiser Hospital, with mother at my side. A young neurologist, after seeing the results of the lab tests, told me I had Guillain-Barre Syndrome, a rare nerve tissue illness.

I could walk, but I felt myself slowly getting weaker. A nurse’s aide seated me in a wheelchair and wheeled me to my room. I was able to walk to my bathroom, but soon learned that I couldn’t get up off the toilet without help.

Three hours later, I was paralyzed from the neck down. A nurse, with great hesitation, as though she were handling something fragile that might suddenly break if she wasn’t careful, arranged the placement of my limbs. With my arm draped over my hip as I lay in a fixed position on my side, with my hand helplessly immobile on my thigh, its fingers fixed in time, I was a stone statue. I couldn’t hold my head up, but, when the nurses turned me over onto my back, I realized I was able to turn my head on the pillow. They devised a system which gave me some ability to act. When I turned to the right, my head made contact with a switch inside the pillow case that called the nurse on duty. When I turned my head to the left, I turned on the TV.

Although my paralysis extended to the far reaches of my body, my doctor said the chances for recovery were good. But he said it would take time because the damaged myelin sheath, the covering of the nerves, grows back only one millimeter a day. Mother and I latched onto the “recovery” part of his prediction. It would never leave our minds.

Mother appeared next morning. She stayed in that room until 4:00 in the afternoon, and did so every single day for the next 45 days I was hospitalized. She traveled the 15 miles from home in a complicated way. Not a confident driver at 80, she drove a few miles and parked in a Santa Monica neighborhood, the limit of her range of comfort. At 5’1”, she needed to grab onto the handrail to climb up onto the first of two buses. After the bus left her off, she walked another three blocks to my room.

Each morning, I strained to hear the special patter of her small steps on the hospital floor outside my door. Then I would see her flash her big smile and sparkling hazel eyes onto me. After she left each day, a sense of helplessness and a heavy sense of life being suspended would creep in overnight. And when she appeared in the morning, it was gone, the way a fog evaporates in the sun all at once.

To relieve the aches and pains of being locked too long in one position, I had to be re-positioned — an arm or a leg, if only a few inches, or my torso pushed into another position. It took a while to find a comfortable spot, and then, even after only a few minutes, the aches could return requiring more exploring for a better spot. To prevent bed sores and the skin infections they caused, the nurses routinely shifted my body and feet three times a day and once at night, arousing me out of my sleep.

Mother became my nurse, with some backup from the beleaguered official nurses who helped her with the more demanding repositioning. She reminded me that during World War II, she volunteered as an assistant to the nurses who took care of the wounded soldiers.

Persistent itches tormented me. When mother wasn’t there to scratch them away, I couldn’t muster the courage to summon one of the busy nurses. But then I discovered a way to get rid of them myself. I focused my attention intensely, like a laser, on any itch that would appear and kept it there until the itch was something else — a rubbing or a vibration or a smudge or a warmth — anything but an itch —and then, in a blip, it disappeared. With each success, I felt a sharp frisson of power within the sea of powerlessness.

Once I was comfortable with the head of the bed propped up, my small mother stood at eye level with me to hold the room phone up to my ear, so I could talk to my Denver law office comrades about my clients’ cases. As we analyzed and strategized, I was back to normal again. For a few minutes I forgot that I was spending another day paralyzed in a hospital bed.

Mother would feed me lunch. Her presence alone, even with small talk, especially the small talk, cocooned me with a confidence that everything was tolerable, everything was doable, as we waited together for the myelin sheath to grow back.

Living in a stationary body, ever in view, stuck in one spot, I tried to fixate only on winning the battle over Guillain-Barre, and my ultimate goal of leaving Denver and being with mother for her remaining years.

At the third week, I saw the first sign of recovery. I could move my big toe. When mother arrived I told her right away. She said, “What did you expect. Jerry? The doctor said you would recover!” She said I was her “soldier,” steady and brave, ready for anything that may come.

After a month and a half of hospitalization, my doctor allowed me to return to Denver. He told me that at a Denver hospital, I could start my physical therapy, the final phase to recovery. On the appointed day, my feet were strapped onto the footrests, my seatbelt buckled tight, and I was wheeled out of the hospital. A good friend, who manipulated my body in and out of seats and executed other grunt work, joined mother and me on the flight. We were happy and light-hearted, celebrating the beginning of my recovery. I felt like a grammar school kid again, moving up to the next grade.

At St. Joseph’s Hospital, my muscles gradually came to life and I gathered strength. The stone statue metamorphosed, over the next six months, into a bona fide human being, well enough to end his long exile and move to Santa Monica.

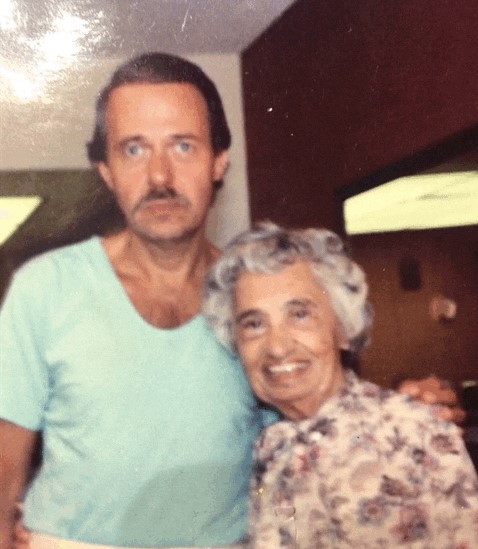

I found an apartment a couple of miles away from mother. I studied day and night for months for the difficult three-day California bar exam. After I passed, I got a job with a small Santa Monica law firm. The workload I took on demanded much more than a typical 40-hour work week, often spilling into the weekend. Still, mother and I checked in by phone every other day, and often enjoyed some of the tantalizing cultural offerings available in Santa Monica and L.A. Even when I suggested going to one of the radical avant-garde movies I liked, she’d quickly say “yes.” Sometimes we’d decide to go to a movie, restaurant or a play on the spur of the moment. We also went to all the family gatherings, whether celebrations or funerals. And so it was that for the next ten years, I realized my vision of a life re-united with mother.

During one of our checking-in phone calls, she interrupted me and said, “Jerry, we haven’t seen each other for two weeks!” We immediately agreed to set aside one day of the week to be sure to be together.

Although not religious Jews, we turned to the ritual of Friday night dinners, the start of Shabbat. Each Friday at sundown, mother, glowing with contentment and immaculately dressed, lit the two white Shabbat candles, sitting tall in two oak candlesticks. Nearby, the regally braided brown Challah bread rested on a white, gold-rimmed, oblong serving plate.

As her mother had before her, she made the blessing of lighting the Shabbat candles, first reaching out her arms to the candles’ flames. In a slow embracing motion, she brought her hands back and covered her eyes with her palms three times. The last time her hands remained over her eyes as many moments went by, during which I sometimes I heard a brief, stifled cry. She then swayed from one side to the other, along with a sigh or two. Inside those silences and sways and sighs, I discovered a new relief. I sang the blessing of the arrival of the Sabbath in Hebrew, which I had learned by a kind rabbi who recorded it on a cassette tape, and we then sat down for the dinner she had prepared.

Nothing much had changed with mother in the months after I found her unconscious in the entry hall. I was living with her for the first time since I was a teenager. She was still the matriarch of the family, the one who planned and organized the birthday celebrations of her two sisters and three brothers and their spouses, the one who set the date and time for the celebrations, the one who selected the fancy restaurant. When her sisters and sisters-in-law complained to her about their disagreements and bruised feelings, she listened carefully and calmed the waters. She wanted peace for everyone. They called her the Henry Kissinger of the family.

As it had been for decades, the social highlight of her week was bridge with her serious card-playing friends — three nattily dressed ladies in their seventies and eighties, coiffed for the occasion. I remember once I came home early from the law office, and said, “Good afternoon, everyone!” They reluctantly raised their eyes from their cards, and nodded with faint smiles in my direction, barely noting my arrival.

Every morning mother opened the Los Angeles Times to “Goren on Bridge.” She meticulously folded the paper to expose only the Goren article, like an unframed painting, and wedged it firmly under the side of her breakfast plate. After figuring out the problem Goren posited, she explained with excitement, how the hand was played. With her mother-to-little boy sing-song teaching voice, I admit to sometimes squirming in irritation. (I can’t say why exactly, but I think it evoked my teenage years, and being so annoyed whenever she persisted in treating me like a little boy) Or else I was delighted—proud that, at 91, she was able to stand firm in the world of bridge. Irritated or proud, nothing in between.

One weekday afternoon, I was in the entry hall, waiting to drive her to her bridge game when she presented herself for my approval with her, “Here I am, let’s go!” look. She asked, “How do I look?” Her silky-soft grey hair was in place—perfect, a little wave on each side. She had applied a faint amount of rouge to her cheeks and was conservatively dressed in a silky, long-sleeved beige blouse and black slacks. She looked fine. But she was barefoot! Her bright red painted toenails ten little fires on the dark brown floor.

Shaken, I deepened my baritone into my base range, where quavers never accompany my words and I sound firm and strong. Mother would be frightened if she saw that I was upset. Mustering up a smile, I asked, “Mom, you couldn’t make up your mind on your shoes? —from your hundreds?” She looked down at her feet and said, “Oh, I forgot,” spun around on a dime, and took off to the bedroom, as though forgetting to wear shoes was a trifle, like forgetting to click off the bedroom lights.

One morning I saw her seated at the kitchen table with her breakfast partner, “Goren On Bridge,” but instead of being displayed in its usual folded up way, nudged into the side of her breakfast plate, it was opened and held high. I couldn’t see her behind the newspaper. Then she poked her head from around the edge and smiled at me in a benign-shy way. And then quickly disappeared behind it again. As I cooked my oatmeal at the stove, I saw she was puzzling over Goren. She had a blank look. Deep vertical wrinkles appeared between her eyebrows and stayed there. I saw her making a deliberate effort to focus and read the words over and over, but then she gave in, and just stared at it again blankly. Nothing was registering! Goren on Bridge had become as undecipherable as Egyptian hieroglyphics.

With my good-bye hug that morning, as she sat in her chair at the kitchen table, I embraced her long and kissed her hard and buried my face into her neck, too choked up to say anything. I looked back as I left for the office and saw her lost and battered look.

One afternoon, after coming back from Saturday grocery shopping, Felicia, mother’s full-time home care provider, told me mother was ill. She had been vomiting for several hours, not a lot and not steadily, but the yellowish-brown drool never entirely stopped its slow leakage. At the hospital, the consulting surgeon stated that she needed exploratory surgery of her bowel. As she was rolled on the gurney to the operating room, I walked alongside, holding her hand. She was silent, her eyes down-cast, barely open. I gave her a big smile, and said “Don’t worry Mom. You’ll do fine!” With an effort, she slowly rolled her head over toward me and with an exhausted look, said “Just let me go, let me go.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing! Here I was determined to be with her all through her final journey, celebrating her life, her every breath, her every shaky-unbalanced step.

How could she want to leave me?

I always thought that, along with my every day joy of giving her my help, no matter how small, and my clear happiness of walking with her, on each and every step in her downward path, she couldn’t help but want to live and be with me as long as possible.

All I heard now was that she wanted to die. And all she needed was to hear me, the soldier-son, tell her, “No Momma, I need you! Please don’t say that.” She did indeed do well with the surgery, and since she never said anything more about wanting “to go,” I figured she really did want to stay with me, and I proceeded to obliterate the memory of what she had said. I didn’t pause to consider that perhaps I was also obliterating the notion that she had a say in the matter. Or to consider the possibility that I was thinking of only my own needs.

After the thief dementia stole Bridge, I thought I’d try a simple card game I barely remembered from childhood, Go Fish. Players pull two matching cards from their hands, set them aside until all the cards are dealt out. The one with the most pairs wins. She couldn’t understand the rules. A few months later, even the TV was not understandable. She stared at the picture as if she were mesmerized by something going on across the room, the way one would relax looking at drifting white clouds over the blue ocean.

In her last year, she was in the hospital for observation of her out of rhythm heartbeat, hooked up with wires running from the patches on her chest up to the overhead cardiac monitor and its continually flowing waves, as well as to an intravenous feeding needle in her forearm. She was too weak to feed herself. When the Nurse brought a fork with food close to her mouth, she blew on it. The nurse gave up on feeding her.

I told the nurse, “You should have encouraged her to eat.” She quickly responded, “Well, we have to respect the patient’s wishes. There’s a time when they want to go.” Angry and offended, I said, “I’m her son. I know what she wants. How do you know she wants to go?” “It’s all over her records,” she huffed. She went, citing her extensive chart, “Look, here’s just one of many of them, “Patient wants to die.”

True, when I had walked alongside the gurney, mother had told me a year ago, “Let me go.” Now the nurse was telling me that mother was saying the same thing to her doctors. I suddenly flashed back on what Dr. Winograd, her primary care doctor, told me a few years further back in her office, “Your mother wants to die.” Taken aback, like someone had just shoved me hard off my feet, I said, “She never told me that!” Patiently and softly, the doctor told me, “She tells me that every time she comes in.” I had blasted all that out of my consciousness as well. I told the frustrated, so-kind doctor, “I have the power of attorney, and I, not you, decide that.”

Now, right in front of me, was that Nurse’s self-righteous face, whose expression said it all —“I’m mercifully granting your mother’s wishes.” I told her “get out of the room” and “don’t come back to my mother’s room again!” Alone with my mother, she only needed a little coaxing to take a bite. She accepted a little ice cream on a spoon and then the rest of the cup, and another helping as well. See! Absolutely no problem with her eating!

On the visitor’s avocado leather chair, my mother’s hospital records lay open to the part the nurse had read to me. But she hadn’t read to me what followed: “patient has had cardiac failure for at least three years. She has survived this long only because of the meticulous care of her son.” It was signed by Dr. Winograd.

When the loudspeakers announced the end of visiting hours, I suddenly felt a need to stay with her all night and told her so. That day she had spoken only a few words until then — a “Yes” or an “okay” —but now her voice emerged with its old confidence together with her melodic mother-to-son coaxing, “You can sleep here in this bed next to me. No one else is sleeping there.” But I wavered, begging off with excuses of not having pajamas and tooth brush, floss, where to put my dentures. Back at home, I thought of her alone at the hospital, abandoned by me.

One day after she had come home from the hospital, Aunt Esther, her sister, made me furious. As I was lamenting mother’s flagging mentality, she interrupted me and said, “She’s in pain, Jerry.” Puzzled, I objected, “What do you mean? She’s never in pain.” Aunt Esther explained, “She has mental pain.” I raised my voice, “No she doesn’t! I live with her, I should know.” My strong willed Aunt charged ahead, “You’re never here.” She was not entirely wrong because in the daytime only the home care people are with her. I was in my office and not there at all.

I had to admit it to myself, the objective facts were overwhelming. I was refusing to accept my mother’s wishes to die. Perhaps I considered my needs paramount. Yes, I was protecting her to keep her alive longer, but was it just to protect myself by keeping her here, firmly in my life? Was I becoming my father, adopting his role as the ruler? And was mother replaying her role as well? Although still asserting her right to speak up, telling me on the gurney, “Let me go,” but in the end, like always in deference to father, she succumbed to silence and obedience, her final obedience — never again daring to tell me “Let Me Go.”

After Aunt Esther left, I realized I forgot to tell her something important about what would happen in the evening that would complete the picture of what I knew about my mother’s state that no one else did. Actually, it happened in the middle of the night. Although, it was true that in the day time I was not at home, there in the evenings, sleeping in the guest room on a comfortable-enough hide-a-bed, I could actually be of help to her. At the ready. A long hallway separated our rooms. I kept our doors ajar so I could hear her. Sometimes her cry of “Jerry!” awakening me was full of gusto, a mother’s command that pulsed through me. In alarm mode, I bounded over to her.

At first, the calls were for me to help her get up off the toilet. Facing her in a kind of embrace, I placed my hands under her armpits and told her to grab my arms, at the elbows. I choreographed the scene, all the while trying to persuade her that I needed her strength too, though she had none, to get her up on the “UP” of “One – two — three and UP!” In our hurray-victory! I went on babbling about things, anything. “Look at how nice and clean that white rug is!” The more I talked, the more I strove to take our minds off her loss of dignity. She was also too weak to wipe herself. My babbling increased ever more in this toilet task. Soon afterwards, she needed help walking back to the bedroom, one hand on my arm, marching along, with little step-stomps, her own special drum beat.

Sometimes in the night she would call me, just wanting to be with me and asking me to stay with her. Plenty of room — my parents had joined two double beds which became a bigger than king-sized bed. Once, I heard her faintly calling out in Yiddish, “Mamala, Tatala” (“Mommy dear, Daddy dear”) over and over. I came in and comforted her and patted her and then held her hand, saying, “It’s O.K., It’s O.K.” She became calmer. “Don’t leave!” she demanded. I lay down next to her, she facing the window and the Santa Monica Mountains beyond, and I behind her sleeping and hovering nearby. During the night, she occasionally whispered, “Don’t go away.”

June 22, 6:00 PM

I arrive home from the office, wrung-out tired. Lydia, the late afternoon home care provider, tells me that mother had been vomiting. But not very much. Momma is in bed propped up on white pillows. She looks unaware of any problem. I kiss her flaccid cheeks and lightly hold her chin within my outstretched fingers. She looks so tired. Her mouth moves toward a smile, but doesn’t quite make it. She says nothing. But I know that her eyes on me is enough to comfort her.

I phone Dr. Winograd, but she is away for a few days. Her nurse gives me the name and phone number of her on-call doctor. I call and leave a message on the machine. She calls back in ten minutes and asks what medications Momma is on. She says she never heard of the new heart medicine, the result of a recent hospitalization. I spell out the pharmaceutical name on the bottle. She says it sounds like a tranquilizer, but I tell her Momma is not on tranquilizers. I wonder if the pharmacy made a mistake and this prescription is the reason she is vomiting. She agrees that’s a possibility, and says, “Well, you could bring her to the ER now or wait for the morning as the vomiting may stop overnight. It’s your call.”

I am afraid of waiting too long. The last time she vomited, I delayed taking her to the hospital because I thought it would stop on its own. The next morning, the doctor said the problem was a blocked bowel and that if I had delayed any longer, she would have died.

I hold her shoulders: “Momma we’ll go to the hospital to stop the vomiting. I’ll be there with you, like always.” She says nothing. But then she looks at me with a sudden clarity and animation. Her eyes fix on me as if she is seeing more, much more than my physical presence.

6:30 P.M.

I phone 911 and in minutes five emergency medics, all over six feet tall, troop into our home. I stand close to Momma as one of them takes her vitals, but as I reach over to hold her other hand, the giant barks, “Don’t touch her! I’m taking measurements!” When he is done, I hold Momma’s hand. I tell her I will be at the ER, like always, about ten minutes after she gets there.

They march off, a column of grim faces, with Momma on a stretcher, with no farewells, like they’re leaving a battlefield. I want to say “Take good care of her,” but don’t. I don’t want to sound foolish. I yell out, “See you soon, Mom!”

I decide to take a book of poetry for a change to read at Momma’s bedside while we wait for the usual lab test results and then the doctor’s assessment. I’ll read aloud; she’ll hear my voice and feel comforted. It takes me a long time to find the poetry books as they are mixed in with all my other books. I keep pausing to look at the titles of books I’d forgotten about. My long day at the office is catching up with me. I need to hurry up. Finally, I grab a book I hadn’t read yet, “The Poetry of Freedom.”

7:15 P.M.

I arrive at the emergency room. The reception clerk asks who I came to see. I tell her, and add, “My mother.” She tells me to have a seat. This is the first time I am told to wait outside the emergency room. The clerk says a doctor will soon speak with me. But I’m puzzled. The lab results couldn’t possibly be available already, so soon after Mother’s arrival. Maybe this clerk is new and not familiar with the procedures.

I usually just go directly into the Emergency Room and find her in one of the hospital beds, curtained off from the other patients, already hooked up to cardiac monitors and intravenous feeding. Why was I directed to have a seat outside the Emergency Room this time?

After two minutes, I lose patience and walk toward the big metal automatic swinging doors that open out toward you. They fling open with a loud bang against the wall and I pass through. I stop the first nurse I see and ask her where my mother is. The reception clerk catches up with me and points to a nearby sculpted, massive oak bench with a high back, like the ones in the California missions, and tells me to sit down in it. She says the doctor will be right out.

8:00 P.M.

A young doctor comes by. He sits down next to me. He looks at me calmly, seemingly in a routine way. “Your mother had…” But then he hesitates, and his eyes shift away a few degrees to the side and downward. His voice becomes softer and his words come out between long pauses. “Your mother………………………….was brought in …….…………………………..from the ambulance……………………………… there was an unfortunate event…………………………………….….she was unable to……..……….…………………………” He stops. A voice asks, “Doctor, are you trying to say my mother died?” Quickly, he says, “Yes.” A long “Noooooooooo!” howls out of me, a howl to the universe. A howl of the end. Of no more.

The doctor puts his hand under my elbow and guides me to an enclosed, private room. The outer pieces of me collect themselves. They hear the doctor: Something about the medics in the ambulance, something about momma choking on her own vomit, medics unable to stop the choking, something about “moribund when she arrived at the hospital,” something about trying his best to save her. The vomit was in her lungs. He reasons with my long moans, “Well now, you know she was very old.”

I don’t want to be with him. I want to see her. Someone leads me to the room for the bodies, the morgue. It’s a shorter man, also in a white coat. His head snaps back toward me every few steps, watching. (Choked to Death on her own vomit!) I don’t look directly at him or at anything at all, just straight ahead because I go that way. A walk to my dead mother.

Alone. Without her in the world.

These are my first steps into a different world. (She didn’t choke at home, sitting in the bed. Why did she start choking in the ambulance?) My steps feel different from any before, peculiar, like I am walking on a different earth-planet. Am I hitting solid? I am not sinking so it must be the floor. My steps are taking me to the end of my mother, to the end of my world. My legs seem separate from the rest of me, moving, independently and mechanically — on their own. I am sitting on top of them, and they carry me to her.

Into the morgue. And there lies my mother: Oh Momma, you are so still. On your back, silent. Your usual soft breathing while you sleep — no more. It’s over, this life.

Your hair hasn’t changed — alive in its soft whiteness, some waves left from the last brushing. It feels the same, like nothing’s wrong. Perfectly fine, just a few spots that need to be brushed into place again, and ready to go. (How did your head go when you were choking and choking and choking?) Your eyebrows, long and naturally sweeping in their arching, now droop downward in a rebuke to your stubbornly closed eyes.

I rest my head upon your stilled, little body, the body that used to glide about me. Your arms lie stiff and straight and lengthwise, glued to your side, at death’s attention. (How did they set you down here?)

Your hands. I used to tell myself I will miss your hands the most. Mine became so dependent upon yours from my earliest moments. You yourself told me: “This is the way you began to walk: first I gave you my hand and you held on and took your first wobbly steps, then soon I gave you one finger to hold (demonstrating her forefinger) and after that you walked on your own.” Now those hands are available to me for the last time. But it wasn’t meant to be like this. I was to be with you in your dying. You were to hold onto comfort and ease and departing life through the constancy of our held hands–the way we always took leave of each other, through a last touch. (How did your divine hands move during the choking and gasping, over and over?)

Yes, the skin of your hands still feels like liquid-smooth river stones. As always, I can’t stop myself from rubbing my thumb softly over them, in slow circular movements, over and over, as I hold your whole hand, bedded in mine. I do not do this too long as I know how annoyed you become with my persistence, in my fascination for the feel of the stones and the river moisture melded into your skin. I stop and hold still, content as before, with having your hand lay quietly in mine, and I want to think I am refreshed as before. I try to hold on to this feeling I will never have again. (What was your very last gasp for air like, Momma? What were you thinking?)

8:30 P.M.

In her bedroom. Her odor still prevails — acrid, filigreed with a sweet scent. It hangs on heavy like a suspended liquid. I slide the window shut tight into its casing and seal it, shutting in her air and keeping it in the room. I will share her odor and the secret of it with no one — that she is still here — in her life’s trail. I breathe her presence in. As I walk, I try to glide like a fish swimming in the sea of her scent, careful not to ripple her away. Finally, I go into her bed, within the sheets and upon the pillow where she last slept. Her skin’s last touch upon these sheets now touches mine. Her usual position of sleep on her right side coincides with mine and my cheek sinks into her cheek’s last push into the pillow. And so I grab and cling and sink into what remains. There, where I someday hope to die.