A very important piece of advice a retiree or prospective retiree can get is this: find something that you like to do and do it.

Why is this good advice?

Well, many retirees have devoted their lifetimes to a particular occupation, industry, or organization. Then bang! Retirement. Suddenly their routines are discontinued. Just as suddenly their identities, so thoroughly invested in the occupations and people with whom they have been associated for decades, are altered, even threatened. That is not a safe place to be.

Some retirees never look back. They walk out the door happy to be free. No identity threat for them. The “find something you like” advice applies, however, as much to them as it does to those who regret leaving the store, school, firm, or team.

Why? The couch beckons. “Binge watch,” invites the TV. Junk food issues its siren call. “You are free to do nothing,” suggests a deceptive and unfriendly spirit. “Every day is a week-end day,” promises the muse of lethargy.

The result can be boredom, ennui, depression, unwanted weight gain, dissatisfaction, and worse, ill health. This bad stuff can be avoided when one finds activity one likes to do and does it. That is a safe place to be.

One safe place, one something that could bring great joy and a modest amount of income is the Standardized Patient (SP) Program. Here is how it works: The teaching facility, usually a medical school, provides a scenario of symptoms or complaints. The SP volunteer studies this “script” and appears at 20-minute sessions with physician assistants (PAs) in training, med students, or residents in hospital settings. During the sessions, the students interview the SPs to discover symptoms, derive diagnoses, recommend medicines, if appropriate, and suggest follow-up procedures, like subsequent visits.

The scenario will state an identity for the SP, a 66-year-old man/woman, for example. It will provide some family and social history, like marital status, smoking history, alcohol or drug use, and occupation. Symptoms might include pain, elevated sugar, high blood pressure, depression, or sudden weight loss.

Some of this information may be known to the student via a medical record for diabetes or blood pressure history. Other symptoms may be unknown to the student, who must discover them by asking questions and performing checks, like listening to the lungs or conducting a neurological test.

The job of the SP is to study the scenario, learn the contents, and respond to questions. It is also the SP’s job to volunteer nothing unless asked. It is the job of the student to ask—to probe for information and make a reasonable diagnosis.

The med students benefit greatly from this procedure, which is far superior to dealing with videos or mannequins. They get to interact with live patients. The SPs enjoy the opportunity to participate in the training of future medical professionals, and they can earn $25 per hour. Sessions can consist of six 20-minute interviews, spread over a 3-hour period.

The sessions may be filmed and viewed later by students and faculty, or a supervisor may attend the sessions as evaluator. Most often, the SP will also complete a check sheet after a visit, and thus participate in the evaluation of the student’s performance.

Specifically, what is the job of the SP:

-

- Listen and Respond

- Remain in character

- Observe dual consciousness

- Operate the magic if

The SP listens for the med student to check the patient’s identity (name and date of birth) and introduce himself or herself. The SP listens and responds to questions about symptom and health history.

The SP must remain in character. Some of these students will look like college sophomores to a retiree SP. So, the SP may want to help out by volunteering information not asked for, just to be encouraging to the youngster. This volunteering of unsolicited information contaminates the process. The scenario may indicate neck pain. The student’s job is to discover this by asking probing questions of the SP. The SPs job is to respond if asked. On the other hand, the SP does not keep secrets. If asked, “What brings you here today?” it is the SP’s job to reveal, “I have neck pain.” if the scenario/script includes this symptom.

Dual consciousness refers to the SP’s responsibility to manage two personas. One is the identity of the volunteer—a retiree with inclinations to want to participate in the development of future doctors—a noble sentiment indeed. The other is the identity of the patient as prescribed by the scenario of history and symptoms. The SP keeps these two personas separate, knowing they exist, but conscious of the obligation to remain in character during the session. The SP controls the inclination to want to coach.

The magic if, is not really magic, but it is a simple explanation of how the SP can manage the session as “actor.” Never acted before? Doesn’t matter. Here is how the magic if works: If you know what the patient wants, if you know what to do to achieve that want, and if you can do that, you can be a successful SP. If you would like to be relieved of the pain in your leg (your want), if you know what to tell the med student if asked (what to do), and if you can tell the student, “I have a pain in my leg,” (do that) you can be a successful SP! The magic if.

Should anyone want to know more about this dual consciousness and magic if stuff, the very best source is The Actor in You by Robert Benedetti, Boston, Allyn and Bacon, 1999.

Want to pursue an SP opportunity? Call the nearest hospital and/or university medical school and ask if they have a Standardized Patient program. Now that you know about staying in character, dual consciousness, and the magic if, you are a very attractive candidate for the program. My own experience is with the University of South Carolina Medical School, and I love it.

Let your great repurposing journey begin! The doctor is in and you are helping.

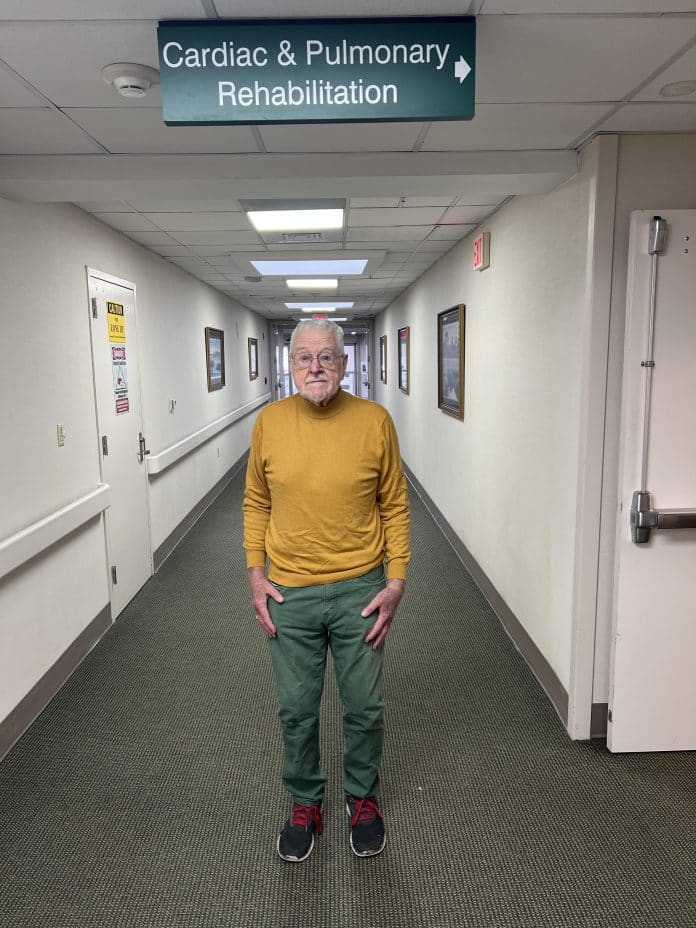

In conclusion, a personal note: I have a great affection for PAs. Three years ago, it was a PA who discovered my heart murmur after a physician had missed it just days before. I owe the gift of life to that PA and to the doctors who gave me a new bovine aortic heart valve. I am now part Bessie. Moo! At the University of South Carolina Medical School, I have observed the performance of excellent PAs in training. That “great affection” now includes admiration for them and for the superb training they receive at the USC Med School.