Although I was just a boy during World War II, I had the remarkable opportunity in 1945, when I was just 14, to work with US Military leadership. By that time, I had already experienced the war from a unique perspective: I was the son of the Russian Jewish refugees, born and raised in wartime Japan.

My parents had each left Russia early in the 20th century: my mother as a child with her parents, fleeing Odessa. My father left as a young man, fleeing the 1917 Russian Revolution. They met in Berlin where my mother was a music student and my father was pursuing work as a classical musician. Soon though, they were on the move – from Paris, to Palestine, to the Russian Jewish refugee community of Harbin, China, and eventually to Japan, where I was born in 1931.

Living in Japan as ‘stateless foreigners’ posed its challenges, but even after Japan became an ally of Nazi Germany, we never experienced anti-Semitism from the Japanese. Still, we were quite aware of what was happening in Europe, as a steady stream of refugees made their way through Japan en route to safety in North and South America.

Although war was already raging throughout Asia, it wasn’t until after Pearl Harbor that we experienced war firsthand. My family was living in Tokyo when the US began launching terrifying and devastating fire bombings. But even as we worked with our Japanese neighbors to put out fires and clear rubble, we were secretly rooting for the Allies to win. Japan and Nazi Germany were allied and we hoped that Japan’s defeat would mean defeat for the Nazis as well.

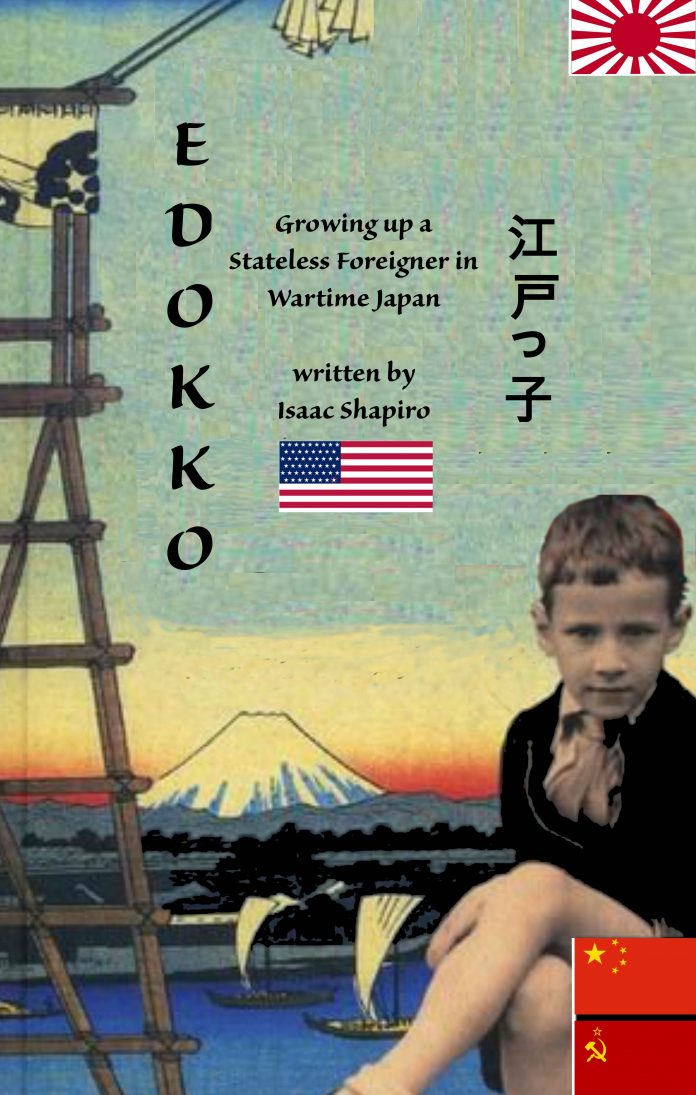

When Japanese surrender came in 1945, I was elated and journeyed to Yokohama Harbor to watch the victorious Americans come ashore. It was a day that would change the course of my life. I remember it in my memoir, Edokko: Growing Up a Stateless Foreigner in Wartime Japan:

“I watched the Americans come ashore, hundreds of them crammed into motorboats, speeding from their ships to the docks. Nothing about that moment was familiar or ordinary. It was unreal and I could feel the excitement. I watched one motorboat zoom toward the dock and soon I could make out the GIs’ faces. A few of the American soldiers seemed to be staring right at me. I stared back.

“Suddenly, I was startled by a voice, much closer and quite loud. “Hi there!” I turned quickly. A tall U.S. Army officer, in his late twenties, had joined me on the embankment. “I’m Captain Kelly,” he said with a broad smile and held out his hand. I took it and waited for him to continue. “Do you speak Japanese?” he asked. “Yes, sir,” I replied. “Good! Then you can help me. I’ve commandeered a school bus but I can’t communicate with the driver. Come with me and tell him where to go.”

This was the starting point of my work with the US Military. Working alongside high level US military officers put me just feet away from the signing of the peace treaty between the U.S. and Japan. And several weeks later, I was selected to accompany a group of officers on their first visit to the devastation of Hiroshima, not long after the atomic bomb had been dropped there. It was an event that has remained seared into my memory, all of these years later.

Again, from my memoir:

“What had once been a thriving city was now, literally, a wasteland, a sea of rubble. Looking clear across the city, from one end to the other, we saw only two burned-out buildings left standing (including, at the epicenter of the blast, the domed building that has become a monument and a world-renowned symbol of the world’s first nuclear air strike.)

“For two hours we were speechless, walking from one pile of rubble to another. I was accustomed to seeing glass fragments after conventional air raids, but I couldn’t find a single cracked or broken piece in this rubble. Picking up a glob of glass that had melted into an unrecognizable mass, I realized that the intense heat generated by the bomb had turned all glass objects into such molten globs. Toward the city center, I saw a lone streetcar making its way across town on the horizon. I saw some pedestrians, hundreds of yards away, walking aimlessly through what must have been streets, but which now led nowhere.”

One year later, I was sponsored to come to America by a US Marine Colonel from Arkansas and his wife. I would fight in the Korean War, become a U.S. citizen, attend Columbia Law School, where I met and married my wife Jacqueline and launch a career in international law. I eventually served as president of the Japan Society in New York City, a position that enabled me to meet and dine with the Emperor of Japan on several occasions.

Although my early days were filled with danger, and my family grew up without the rights of citizenship, I’ve retained a real fondness for Japan and the Japanese people, something that was only strengthened when I eventually learned that the Nazis had pressured Japanese leadership to turn over the Jews in Japan – a request that was ignored.