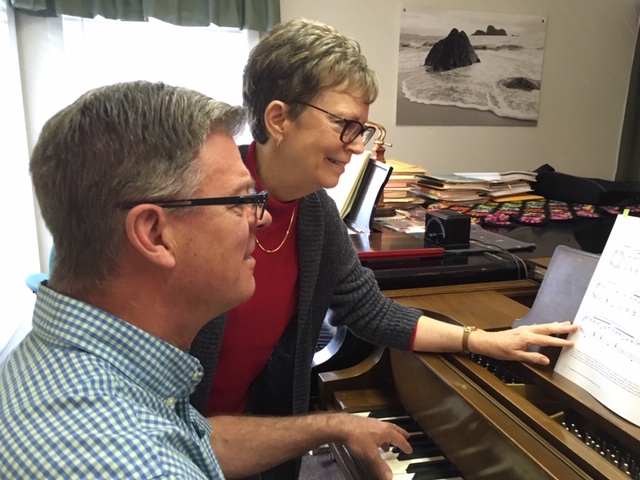

Abstract: Studying piano as an older adult presents special challenges and joys for both teachers and students. This article examines both from the perspectives of Kelly Zuercher, resident pianist with the Colorado Springs Philharmonic and respected teacher, and one of her “senior” students, Fran Pilch.

Kelly: I have taught piano lessons since I was sixteen years old. Initially I accepted students primarily as a way of earning money while I focused on a performance-based track in my high-school and college years, as I was training to be a concert pianist. Many of my peers with similar training went on to have successful careers by focusing on teaching younger up-and-coming students who could potentially develop into performing artists.

Over the course of my career I have had the pleasure of working with some very gifted young students who have become successful professional musicians and teachers. However, I have reaped a myriad of benefits, personally and professionally, by having made the decision early in my career to accept a wide range of students, which has included a number of older students in their retirement-age years.

I have known many piano teachers to be reluctant in accepting adult students because these students often bring years of playing practices and habits which can be challenging to work with, or because these students may harbor years of unrealistic expectations which can frustrate both student and teacher. However, in contrast, I have found my overall experience of working with adult students – especially the adults of or approaching retirement age – to be highly educational and gratifying.

It could be argued that in order to teach successfully, a teacher must adhere to a certain preconceived impression and plan for what the student will achieve during the learning process. However, if that plan is too rigid or narrow, student success may be threatened, discouraged or thwarted – and I certainly have known adult students who have become disillusioned and disappointed in their studies, mainly because those students were not fitting into the “mold” or realm of expectation their teacher had for them.

On the other hand, I have seen great success in teaching piano to older adults, when the plan of study starts with what I consider to be the most essential characteristic that all adult students share in common, which is the desire to enjoy art and to learn something new. In addition I have witnessed amazing talents and accomplishments by these students, when they have been allowed to explore their studies and blossom at their own pace and unique style of learning. Whether the older adult student comes to piano lessons as a beginner, an accomplished player, or somewhere in-between, he or she always chooses to study piano for personal reasons, and in most cases this student is highly motivated and engaged in the learning process.

Over the years of working with older adult students, I have learned there is so much more to teaching than I once thought possible. For example, I never expected to meet and have the pleasure of working with such a large number of truly inspiring older students, such as an eighty-year “young” artist who is presenting her very own full-length solo recital this year, culminating a lifetime of piano study. At the other end of the spectrum, I have another older student who struggles to master the basics of sight-reading notes and ease in playing, but together we always manage to have fun and share some chuckles. And I come away feeling encouraged and inspired because that student has discovered a new sense of accomplishment and joy during this lesson.

Older adults often face some physical limitations in piano playing, which may include arthritis, diminished range of movement in their hands and bodies, and general lessening energy and stamina. However, playing the piano can be extremely beneficial in alleviating many of the symptoms of those conditions by increasing finger and body activity. Moreover, while the effects of playing and studying the piano are known to improve brain activity and ability in all students, the effect on older students can be especially noticeable. The discipline of learning and practicing the piano seems to improve our ability to remember and learn new things, not just in music, but in other tasks which may be new to us. In addition, scientists are still discovering new ways in which music helps to stimulate and reinvigorate the older brain.

Many older students feel they cannot memorize music as well as they once could when they were younger. I have experienced this myself, but at the same time, have observed that as we age we generally learn differently, and thus remember what we learn in a new and different way. While younger players tend to memorize more by sound and muscle memory, we gradually begin to learn and remember via more intellectual means. And often we do have to work harder to learn a new skill, but the satisfaction we gain is so very worth it when we have achieved progress and have learned to embrace and be happy with our progress, knowing we have done our best.

I recall a famous musician who was giving a master class to a group of college piano students, who told a student that every time that student played the piece he was practicing (in this case I believe it was a sonata by Beethoven), he was not only practicing that piece of music, but he also was “synthesizing” something deep within himself – somehow working out the deeper issues and challenges he was facing in life. At its best, the study of music can give us all that kind of richer meaning in our lives if we are open to the challenge. Playing the piano as an older adult is so very worthwhile and I highly recommend the experience!

…………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Fran: Some senior students begin their piano studies after retirement or as an older adult, with no prior training. Most, however, have studied piano at some point in their lives. In my case, I started piano lessons at age 7 and continued through graduate school. This was followed by an extended period of time, as I raised my family and concentrated on my career, when I took no lessons and seldom played classical music. When I approached retirement, I resolved to renew my interest in the piano, and was fortunate to meet Kelly at a Colorado Springs Philharmonic board meeting. I remember passing her a note that asked, “Do you give piano lessons to seniors?” She wrote back, “Yes!”

Having studied with Kelly for three years now, I have no doubt that music has a very special role to play in the lives of senior citizens. Research bears out the importance of keeping our brains active as we grow older. Piano study, or lessons on any instrument (or voice), provide special advantages: students need to read music, transfer what they read to their muscles, interpret music on a variety of levels including dynamics and rhythm, and train their eyes, ears, and hands to react as we want them to react. Playing the piano is a complicated endeavor, and involves many parts of our brains, plus multiple talents and skills. Memory is an important tool, but it is not the only one. Emotional maturity and dexterity of our fingers and wrists are also important as we seek to improve our ability to play the piano.

A survey of Kelly’s “older” students as to why they study piano at this stage of their lives was very illuminating. One student said, “As a child, I definitely didn’t enjoy my lessons. I resumed piano study in earnest when I turned 50. Piano is completely different for me now. I am passionate about music and the opportunity for self-improvement. I am a firefighter. Piano study is a hugely important part of my present life.” Another student remarked, “It’s so interesting. Now there is NO pressure! I’m not trying to please anyone but myself. It’s all for me now. In a way it’s therapy!” Another said, “For me, it’s all about creativity. I want to use both sides of my brain as I get older.” Every respondent noted that studying piano at this point in their lives was qualitatively different from study as a child. Every respondent noted that time practicing was not a “chore,” as it was previously – now it was a pleasure and a chance to “lose oneself in music.” While perfection was a goal for some, most just reveled in the joy of music and the accompanying sense of accomplishment!

This joy does not, however, come without challenges. In my sixties I noticed that my little finger on my left hand was curling toward my palm, and soon I could not straighten it. This condition, diagnosed as Dupuytren’s Contracture, sometimes appears in older adults. Although it was slightly improved after a visit to a hand surgeon, my finger will never be “normal.” I have to compensate for a feeble little finger when I play certain passages in piano scores. My vision has also been in decline. Some students comment that they used to be able to reach an octave or more, but can no longer do so. Others find that their finger dexterity is compromised by arthritis. The most common issue for most of us is our reduced capacity to memorize. I used to be able to memorize a piece extremely rapidly. Now, it may not happen at all! The plus side is that we all say our life experiences seem to allow us to better visualize pieces as a whole and to “feel” musicality.

Much of the anecdotal evidence of the benefits of studying piano as a senior citizen is borne out by recent research. For example, “[p]laying music reduces stress and has been shown to reverse the body’s response to stress at the DNA-level.”[i] Musical study can improve processing speed and memory after a relatively short period of lessons and practice.[ii] Findings from a study at the University of Montreal and cited in the journal Brain and Cognition, showed that “participants who played an instrument reacted up to 25 per cent faster to external stimuli such as sound and touch than their non-musical counterparts. The study explains that playing music requires the use of multiple senses simultaneously, which strengthens brain pathways to enhance reaction time.” It also appears that the study of music may counteract hearing problems in seniors.[iii]

Research is illuminating the relationship between memory and music. The salience network of the brain “remains an island of remembrance that is spared from the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease.”[iv] As a volunteer who plays the piano in an Alzheimer’s facility, I have noted that even severely impaired patients can sing along as I play familiar songs, often remembering the words and tunes when they cannot remember the names of everyday things.

Encouragingly, you don’t have to be an expert pianist to reap tremendous benefits. According to a study at Northwestern University, “Playing the piano helps to build neural connections, improving memory and clarity. Even a small amount of music provides long-lasting effects on the brain.”[v]

Retirement gives us the opportunity to spend time on endeavors that we didn’t have time for previously. When we study piano we are constantly learning and growing! We are setting goals, and reducing stress, even as we improve cognitive and motor skills. Most of all, we are enhancing the quality of our lives!

Because studying the piano engages so many of our abilities and skills, and may even serve to address stress in our lives, it is an extremely valuable activity for the older student. I would like to encourage senior citizens to consider embarking on this adventure, regardless of whether they are new to the piano, or have studied previously. I am convinced that all will benefit enormously! What a sense of accomplishment mastering a piece of music brings to the senior piano student!

[i] ‘Why Play Music – Seniors,” available on the internet at https://www.nammfoundation.org/articles/2014-06-01why-play-music-seniors, Dr. Barry Bittman.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Parbery-Clark A, A.S. Kraus N., Musical Experience and Hearing Loss: Perceptual, Cognitive and Neural Benefits in Association for Research in Otolaryngology Symposium,. 2014, San Diego, CA, cited in “Why Play Music,: op. cit.

[iv] University of Utah Health, “Music Activates Regions of the Brain Spared by Alzheimer’s Disease,” ScienceDaily, 28 April 2018.

[v] Available on the internet at https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3814522.